Persian Proverbs from Shahnameh

نوشدارو بَعد از مَرگِ سُهراب

nušdâru ba’d az marg-e Sohrâb

Lock the barn door after the horse is stolen

nušdâru ba’d az marg-e Sohrâb

Lock the barn door after the horse is stolen

یکی از سَختیهایِ زبان در سُطوحِ پیشرفته این است که زبانِ هر کشور ریشه در گُذشته، داستانها، رَوایتها و سُنتِ آن کشور دارد. شاید شما واژهها، دَستور و اِصطِلاحاتِ زبانِ فارسی را بدانید، با این حال، در فهمیدنِ مَنظورِ ایرانیها دُچارِ مُشکل شوید. چرا که در گفتگو به یک داستان یا نامِ خاص اِشاره شده است که شما آن را نمیدانید، اما برای ایرانیها یک خاطِرهی مُشتَرک را زِنده میکند. مَعمولاً داستانهایِ مَذهبی از قرآن و روایتهای مَذهَبی، داستانهایِ اُسطورهای از شاهنامه یا داستان ِ عِشقهایِ نافرجام مَرجَعِ این اِشارات هستند. اگر از اِشاره در اَدَبیات استفاده شود، آن را تَلمیح میگوییم. اما در زبانِ روزمَره نیز ممکن است از اِشاره کردن به یک رُخدادِ خاص برایِ بیان کردنِ مَنظورِ خودمان استفاده کنیم. یکی از رایِج ترین اِشارات که بین همهی گویشوَران فارس زبان در ایران، اَفغانستان و تاجیکستان استفاده میشود، «نوشدارو بعد از مَرگِ سهراب» است که از داستانهایِ شاهنامه گرفته شده است. برایِ این که کاربُردِ این جمله را یاد بگیریم، بهتر است اول داستانِ آن را بدانیم.

Sometimes, you may need help understanding what a Farsi speaker intends to say despite knowing the vocabulary and structure of the sentence. They are probably mentioning a particular name or a historical event that you do not know about, but it is rooted in the Persian speakers’ collective memory. The reference of these allusions can be religious stories from Quran, mythological or love stories, and historical events. Using allusions in Persian literature, called talmih in Farsi, and colloquial Persian is common. One of the most popular allusions used by Farsi speakers in Iran, Afghanistan, and Tajikistan is “nušdâru ba’d az marg-e Sohrâb,” which means “panacea after Sohrab’s death.” Before learning the signification and function of this phrase, we’d better read the story of Sohrab and Rustam from the Persian Epic called Shahnameh.

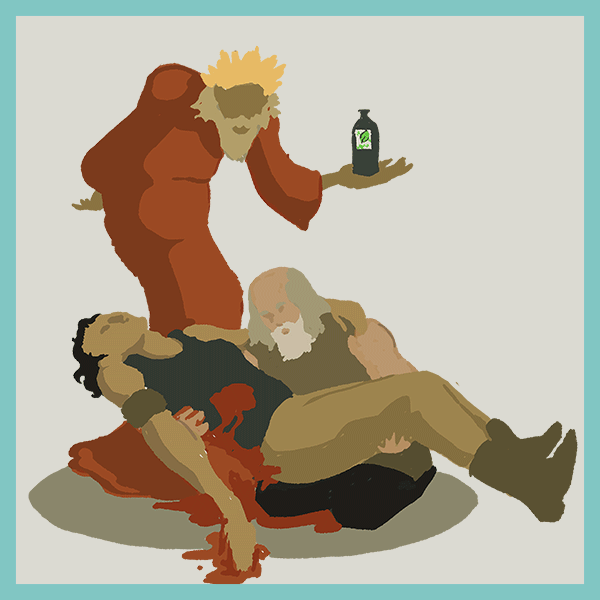

یکی از سَرشناسترین قَهرمانهایِ شاهنامه، رُستَمِ دَستان است. قَهرمانی جَنگاور و باهوش با خَطاهاییِ بزرگ. یکی از تِراژدیهای شاهنامه مُبارزهی رُستم با پِسرش، سُهراب، است. رُستم قَبل از تولّدِ سُهراب، هَمسرش، تَهمینه، را تَرک میکند و به جنگ میرود. برای همین، پسرش را نمیشِناسد. سُهرابِ جوان در یک توطِئه، مُبارزهی تَن به تَن با رُستمِ پیر را میپَذیرد. پدر و پسر یکدیگر را نمیشِناسَند و هرچه سُهراب تَلاش میکند تا اسمِ رُستم را بداند، مُوَفَق نمیشود. آنها یک روزِ کامل میجَنگند. رُستمِ پیر که در برابرِ سُهرابِ جوان خسته شده است، با حُقّهای مُبارزه را به روز بعد مُوکول میکند. در روزِ دوم نیز رِستم به شِکَست نزدیک است اما در نَهایت باز هم با نیرنگی سُهراب را زَخمی میکند. بعد از زَخمی شدن، بالاخَره سُهراب نامِ پدرش را به زَبان میآورد و میگوید روزی پدرش، رستم، اِنتِقامِ او را خواهد گرفت. اینجاست که رُستم میفهمد چه اشتباهی کرده است. کسی را نزدِ کِیکاووسشاه میفرستد تا برای دَرمانِ سُهراب به او نوشدارو بدهد. کِیکاووس که از بودنِ دو پَهلَوان کنارِ هم میتَرسد، در فرستادنِ دارو دِرَنگ میکند و سُهراب پیش از رسیدنِ نوشدارو دَرمیگُذَرَد.

Rustam-e Dastân is one of the most eminent heroes of Shahnameh, an intelligent warrior with unforgivable mistakes. The battle between Rustam and his son, Sohrab, is among the most poignant tragedies in Shahnameh. Rustam leaves her wife, Tahmineh, to attend a war before their son’s birth; therefore, he does not know Sohrab. Years later, Sohrab, a young fame-seeker warrior, accepts hand-to-hand combat with Rustam. A conspiracy, of course. Rustam and Sohrab do not know each other, and Sohrab’s attempts to figure out his opponent’s name remain fruitless. They start the combat, and a whole day of fighting tires old Rustam. He beguiles young Sohrab to cease the fight and pursue it the next day. On the second day, Rustam wounds Sohrab with another trick. When Sohrab cries out that his father, Rustam, will take revenge for his death, he finally recognizes his son and regrets what he has done. He pleas for nušdâru, but king Keykâvus, scared of the two heroes’ unification, lingers to send it. Sohrab succumbs a few hours before the medication arrives.

در اَدبیاتِ کِلاسیک و مُدرن فارسی بارها به این داستان اشاره شده است. در فارسی امروزی هم «نوشدارو پس از مرگِ سُهراب» به عنوانِ یک ضَربُالمَثَل استفاده میشود. مَعنی آن کمکی است که دیرتر از موعِد به دست ما میرسد و دیگر فایدهای برای ما ندارد، یا کاری است که خیلی دیرتر از آن چه که باید، انجام میشود. نمونههای زیر به فارسی آموزان کمک میکند تا کاربُردِ این مَثَل را بهتر یاد بگیرند.

The tragedy of Rustam and Sohrab is alluded to in various ways in modern Persian and classic poetry. “nušdâru ba’d az marg-e Sohrâb” is also used as a proverb in colloquial Farsi to bring up the idea of a help that is received after the problem is solved or an act that is taken too late and in vain. The closest English equivalent to the proverb can be “locking the barn door after the horse is stolen;” however, the Persian one seems to have a stronger connotation referring to a tragic death and is mainly used for severe problems. Following examples from Persian poems and daily conversations can give Farsi learners a better hint.

در شعر

1)

فَرُّخی سیستانی

چون تَبه گَشت مرا حال بدین سان، چه کُند

نوشدارو که پَس از مَرگ به سُهراب دَهَند؟

In Persian Poems

1)

Farroxi Sistâni

čon tabah gašt marâ hâl bedinsân, če(h) konad

“nušdâru ke(h) pas az marg be sohrâb dahand?”

Now that my mood is ruined, how can nušdaru after Sohrab’s death help me?

2)

شَهریار

آمدی، جانم به قُربانت ولی حالا چرا؟

بیوَفا، حالا كه من افتادهام از پا چرا؟

نوشدارويي و بعد از مرگ سُهراب آمدی

سَنگدل اين زودتر ميخواستي، حالا چرا؟

2)

Šahriyâr

âmadi, jânam be qorbânet vali hâlâ čerâ?

bivafâ hâlâ ke(h) man oftâde(h)-am az pâ čerâ?

“nušdâruyi-o bad az marg-e Sohrâb âmadi.”

sangdel in zudtar mixâsti hâlâ čerâ?

You came, my life yours, but why now?

Faithless, why now that I can’t stand on my feet?

You are like nušdaru but coming after Sohrab’s death,

Why did you come so late if you wanted us to be together?

گُفتگوی یک

نیما: نَرگِس! بالاخره بانک با درخواستِ وامم مُوافقت کرد.

نرگس: چقدر خوب!

نیما: فایدهای نداره. اینقدر دیر دادن که مجبور شدم ماشینم رو بفروشم.

نرگس: نوشدارو بعد اَز مرگِ سهراب.

نیما: آره، متأسفانه.

goftogu-ye yek

Nimâ: Narges! belaxare(h) bânk bâ darxâst-e vâmam movâfeqat kard.

Narges: čeqadr xub.

Nimâ: Fâyide(h)-i nâdâre(h). inqadr dir dâdan ke(h) majbur šodam mašinam ro befrušam.

Narges: “nušdaru ba’d az marg-e Sohrâb.”

Nimâ: âre(h), mote’asefâne(h).

Dialogue One

Nimâ: Narges! Finally, the bank accepted my loan request.

Narges: Wow, great.

Nima: Useless. It was too late, and I had to sell my car.

Narges: “nušdaru after Sohrab’s death,” then.

Nima: Yep, Unfortunately.

گُفتگوی دو

فاطمه: ویزای مامان پری اومد، میتونه برای اِدامهی دَرمان بره آلمان.

سعید: تَلختر از این میشه؟ دیگه خیلی دیر شده. سرطان همهی بدنش پخش شده.

فاطمه: شاید هنوز امیدی باشه.

سعید: نه متأسفانه. نوشدارو بعدِ مرگِ سهرابه.

goftogu-ye do

Fâteme(h): vizâ-ye mâman Pari umad. Dige(h) mitune(h) barâ-ye edâme(h)-ye darmân bere(h) âlmân.

Sa’id: talxtar az in miše(h)? dige(h) xeyli dir šode(h). saratân hame(h)-ye badaneš paxš šode(h).

Fâteme(h): šâyad hanuz omidi bâše(h).

Sa’id: na(h) mote’asefâne(h). “nušdâru ba’de marg-e Sohrâb-e(h).”

Dialogue Two

Fâteme(h): Maman Pari’s visa is ready. She can finally go to Germany to continue her treatments.

Sa’id: Could it be more bitter than this? It is too late. The cancer is all over her body.

Fâteme(h): There might be some hope.

Sa’id: Unfortunately not. It is nušdâru after Sohrab’s death.

Leave A Comment