Sadeh Festival in Zoroastrianism

Author: Nina Ahmadi, Negar Ilghami

Illustrator: Bahareh Zargaran

جَشنِ سَده

(C1 مُناسب برایِ فارسی آموزانِ سَطح)

سَده یکی از قَدیمیترین جَشنهایِ ایرانی و بزرگترین جَشنِ زِمستانی در میان زَرتُشتیان است. سَده در شامگاهِ دهمِ بَهمن و با اَفروختن آتش در میانِ زرتشتیانِ ایران، افغانستان و هند، و در کشور تاجیکستان به عُنوانِ جشنِ مِلی گِرامی داشته میشود. دربارهیِ پیشینهیِ این جشن داستانهایِ گوناگونی گفته شده است که در اینجا چند داستان را با هم میخوانیم.

Sadeh Festival

(Farsi Level: C1)

Sadeh = sade(h) is one of the oldest Iranian Festivals and the most significant winter celebration among Zoroastrians. Sadeh is annually celebrated on January 30th, forty days after Yalda and Fifty days before Norouz. The festival is held in Iran, Afghanistan, India, and Tajikistan. There are different mythological stories about the history of this celebration; we will read a couple of them in this article.

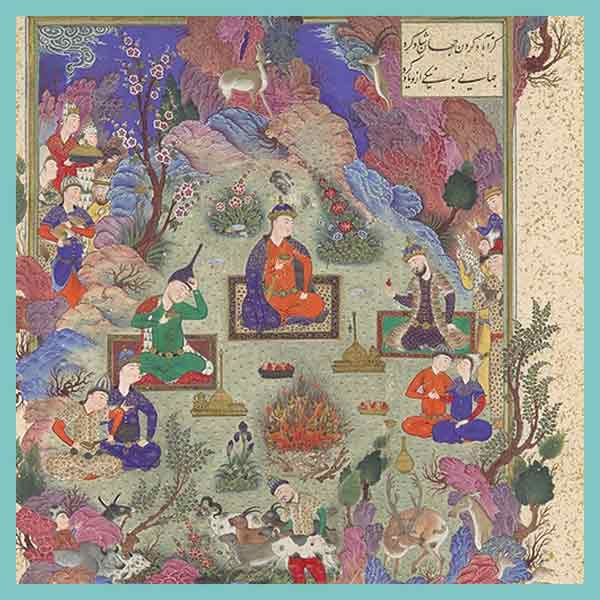

سَده دَر شاهنامه

نام سَده در شاهنامهیِ فردوسی، داستانِ حِماسیِ بَرجامانده از هِزارهیِ پیش، آمده است. بر اساسِ داستانِ فِردوسی، هوشَنگ پادشاهِ پیشدادی، برحَسبِ اتفاق نَحوهی روشن کردن آتش را کَشف میکند. او این روز را سَده مینامد و برای پاسداشتِ آتش با افروختن آتَشی بُزرگ، شُکرگزاریِ پَروَردِگار و نوشیدنِ شراب جشن بزرگی بَرگُزار میکند. داستان از این قرار است:

Sadeh in Shahnameh

Jashn-e Sadeh is mentioned in Ferdowsi’s masterpiece, Shahnameh, the Persian epic written a millennium ago. In Ferdowsi’s narration of Sadeh, Hushang, the king of the Pishdadian dynasty, accidentally discovers how to light a fire. He calls the day Sadeh and celebrates it by lighting a big fire, praising God, and drinking wine. Here is the story:

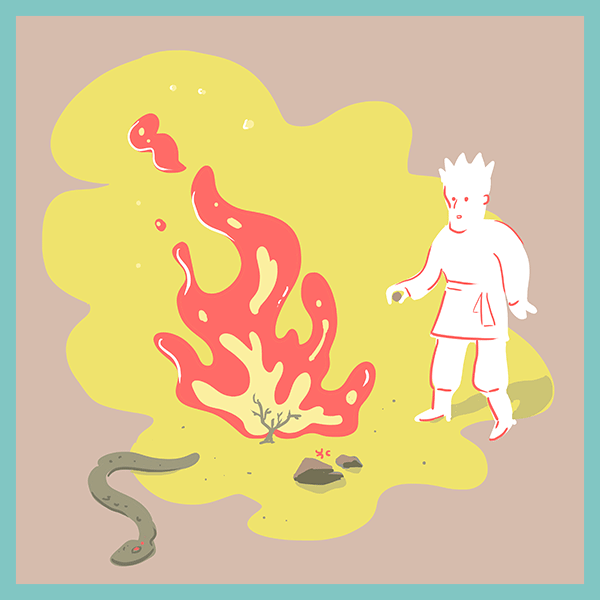

روزی هوشَنگ با همراهانش در کوهِستان در گَردش هستند که ناگهان هوشَنگ از دور مارِ سیاهِ بَدشِکلی را پشتِ صَخرهای میبیند.

One day, Hushang and his entourage are walking in the mountains when they suddenly see an ugly, monstrous black snake behind a rock.

پَدید آمد از دور چیزی دِراز

سیه رَنگ و تیرهتَن و تیزتاز

دوچَشم از برِ سَر، چو دو چِشمه خون

ز دودِ دَهانش جَهان تیرهگون

padid âmad az dur čizi derâz

siyah rang-o tire(h)tan-o tiztâz

do čašm az bar-e sar čo do češme(h) xun

ze dud-e dahânaš jahân sarnegun

A long thing was seen from far behind

Black with dark body, moving quickly

His eyes resemble two bowls of blood

A fire coming out of his mouth could ruin the world

هوشَنگ سنگی به سَمت این مار پَرتاب میکند. از آنجایی که خوب نشانهگیری نکرده، اشتباهاً سنگ به صخرهای که مار پشتش پناه گرفته بود میخورد. متاسفانه مار فرار میکند، اما از آنجایی که سنگها، آتشزنه هستند، بَرخوردشان جرقهای ایجاد میکند و شاخههایِ خُشکِ اَطراف را میسوزانَد. بدینگونه هوشَنگ ساختن آتش را کشف میکند. هوشنگ با دیدنِ آتش آن را نورِ ایزدی و شایستهی پرستش مینامد و برای این هَدیه ایزَد را سِپاس میگوید و آن روز را سَده مینامَد. در فرهنگِ ایرانی، مار نِمادِ اَهریمن و آتش نورِ ایزدی و حقیقت است. اگرچه هوشنگ نمیتواند مار را بکشد و اهریمن را شکست دهد، اما راهِ زنده نگه داشتن حقیقت را مییابد.

Hushang throws a stone to kill the snake. He is not targeting well and mistakenly hits the rock behind which the snake had sheltered. Unfortunately, the snake escapes, but since the stones were flint stones, they spark and light the dried branches around. This way, Hushang discovers how to make a fire. He announces that the fire is “a light from God that should be admired,” and he shows his gratitude to God by calling this day “Sadeh” and celebrating it. In Iranian culture, the snake symbolizes Ahriman, Satan in Abrahamian religions, while fire is a light from Izad, God, that guides us to discover the truth. Although Hushang cannot kill the snake, which means he cannot defeat Ahriman yet, he learns how to search for the truth.

جَهاندار پیشِ جَهانآفرین

نیایش هَمیکرد و خواند آفَرین

که او را فُروغی چنین هَدیه داد

هَمین آتش آنگاه قِبله نَهاد

بِگُفتا فُروغیست این ایزدی

پَرستید باید اگر بِخرَدی

شب آمد، بَرافروخت آتش چو کوه

هَمان شاه در گِردِ او با گروه

یکی جَشن کرد آن شب و باده خورد

سَده نام آن جشن فَرخُنده کرد

jahândâr piš-e jahân âfarin

niyâyeš hamikard-o xând âfarin

ke(h) u râ foruqi čenin hadye(h) dâd

hamin âtaš ângâh qeble(h) nahâd

begoftâ foruqist in Izadi

parstid bâyad agar bexradi

šab âmad barafruxt âtaš čo kuh

hamân šâh dar gerd-e u bâ goruh

yeki jašn kard ânšab-o bâde(h) xard

Sade(h) nâm-e ân jašn-e farxonde(h) kard

The king in front of the creator (God)

Praised God by saying prayers

For gifting him with such a light

He selected the fire as the Qibla[1]

He said this is the Light sent by Izad

Everybody should worship it if they are wise

When night arrived, he lit a fire as big as a mountain

The king accompanied by his entourage

He celebrated that night by drinking wine

Calling that glorious fest “Sadeh.”

[1] Direction for prayer

رَوایَتهای دیگر از سَده

براساسِ روایتی از ابوریحان بیرونی، نامِ جَشن سده از عدد 100 گرفته شده است، چرا که در آن روز، کیومَرث، هَمتایِ آدم در اَساطیرِ ایرانی، صاحبِ صَدمین فرزندش شد و این روز را جَشن اِعلام کرد. اما خیام در نوروزنامه، روایَتِ دیگری دارد. در داستانِ خیام، فِریدون پس از پیروزی بر ضَحاک، پادشاهِ سِتَمکارِ ماربردوش، و آزاد کردنِ مردم آتشی برای جشن بَرافروخت و آن روز را سَده نامید.

Other Narrations about of Sadeh

In another story, Abu Rayhan Biruni claims that “Sadeh” gets its name from “sad,” which means hundred in Farsi. According to his story, when Kiyumars[1]’ hundredth son was born, he called the day Sadeh and celebrated it. But Khayyam in NorouzNameh has another narration. In his story, after Fereydun’s victory over Zahhak, the evil snake shoulder king of Iran, people celebrate their freedom by lighting fire and calling the victory day “sadeh.”

[1] First human in Iranian Mythology

اگرچه این داستانها متفاوتند، اِشتراکاتی نیز دارند: وُجودِ اَهریمَن، مبارزه با او و بَراَفروختَنِ آتش برای شِکست دادنِ تاریکی. بعضی پَژوهِشگران مُعتَقِدند که جشنِ سده تاریخی پَنج هزار ساله دارد، قدمتی بسیار بیشتر از آیینهایِ زرتشتی. جَشنِ سده در میانِ ایرانیانِ قَدیم اَهمیتِ زیادی داشته است و حَتی با وُرودِ اسلام به ایران، از میان نرفته و به همراه نوروز و مِهرِگان بَرگُزار میشده است. اما درایرانِ امروزی، جَشنِ سده بیشتر در میان زَرتُشتیان و در شهرهایِ کِرمان، یَزد، شیراز و تهران بَرگُزار میشود.

Although these narrations may differ in some details, there have significant themes in common: fighting against Ahriman and lighting fire to defeat darkness. Some historians believe that celebrating Sadeh dates back to 3000 B.C., years before Zoroastrianism became prevalent in Persia. Sadeh was highly valued among Iranian, so people celebrated it along with Norouz and Mehregan, even after converting to Islam. Nowadays, Sadeh is mainly celebrated by Zoroastrians in Kerman, Yazd, Shiraz, and Tehran.

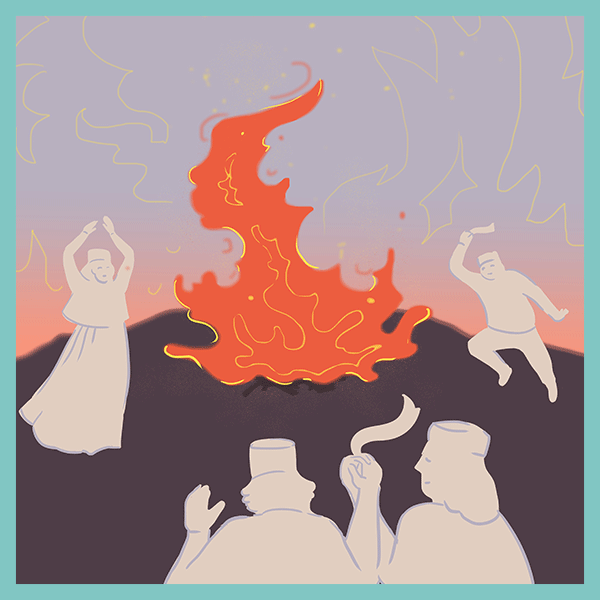

آیینهای سَده

از آیینهایِ جَشن سَده در دوره ی ساسانیان و پیش از آن هیچ اِطلاعی در دست نیست، اما امروزه سده یکی از مهمترین جَشنها در میانِ زَرتُشتیان است. جوانان و نوجوانانِ زَرتُشتی از چند روز قبل از جَشن، به جَمعآوریِ هیزُم پَرداخته و آنها را به مَحَلِ برگزاریِ جَشن میبَرَند. از بامدادِ روزِ دهم بهمن، بانوان در محلِ جشن جَمع شده و سیرُگ (سوروک)، آش مَخصوص، و نانِ سنتی آماده می کنند. مردم در تالارِ شَهر گردِ هم جَمع میشوند. به هنگامِ غروب خورشید، سه تن از موبدان با لباسِ سفید کنار هیزُمها بَخشهایی از اَوِستا، کتاب مُقَدَسِ زَرتُشتیان، و سُرودِ نیایشِ آتش را میخوانند و سه بار بَر گردِ تودهی هیزم میچَرخَند و سپس هیزُم ها را آتش میزنند. گُروهِ موسیقی آهنگهایِ شاد مینوازَند و مردم شُعله ور شدنِ آتش را جشن میگیرند و اینگونه جَشن به پایان میرسد.

Ceremonies

There is not much information about Sadeh’s ceremony before the Sasanians. But nowadays, Sadeh is an important festival among Zoroastrians. A few days before the celebration, young Zoroastrians collect fire woods and camel’s throne for making fire. On the morning of the Sadeh, women get together to prepare traditional foods like Sirog (Suruk), Ash, and traditional bread. People usually wear white clothes on this day. By sunset, all participants stand in a circle around the woods. Then three Mobads[1] in white dresses read some parts of Avesta, Zoroastrians’ holy book, while going around the woods three times. Then they light the fire with the help of young men. The ceremony ends with playing music, eating, and dancing.

[1] Zoroastrians Cleric

Leave A Comment